- Published on

Breaking the Curse of Expertise

- Authors

- Name

- Alex Stephens

- @astephens__

That’s all any of us are: amateurs. We don’t live long enough to be anything else.

Charlie Chaplin

In my second year as an undergraduate, I got a job as a tutor at my university, teaching an introductory programming course. Most of the students in this course were only a year below me academically, and in many cases actually older than me. This was a course that I had done well in the previous year, and felt quite confident that I was well-equipped to teach clearly and intuitively to beginners. However, I found that when I mentioned my teaching job to people, they would often (very tactfully, of course) express their scepticism at the concept of someone tutoring a course that they had taken so recently. In most faculties at my university, undergraduates were not allowed to work as tutors at all, and even in the few where it was allowed, teaching a course the year after taking it was pretty unusual.

In part, I understand where these doubts came from - in many fields, teaching effectively on certain topics requires understanding that goes deeper than the actual content being taught. I found this to be particularly true in my studies of physics, where as first-year students we would often have questions that required significant background knowledge and intuition to answer satisfyingly. However, this is not the case across the board, and certainly wasn't the case in my course, which was self-contained in such a way that it would not tend to provoke questions that went outside of its scope. In short, if you knew the content and knew how to teach, you would be able to teach it well.

The curse of expertise

Our default mindset is to prefer being taught by people whom we consider to be experts, whatever that might mean in the particular context. We want to learn from people with a lot of experience, in the hope that we will somehow be able to absorb their distilled knowledge and wisdom - a hope that, at least at first glance, seems completely reasonable.

However, in many cases, expertise can actually be a barrier to effective teaching. C. S. Lewis has a great explanation of this:

It often happens that two schoolboys can solve difficulties in their work for one another better than the master can... The fellow-pupil can help more than the master because he knows less. The difficulty we want him to explain is one he has recently met. The expert met it so long ago he has forgotten. He sees the whole subject, by now, in a different light that he cannot conceive what is really troubling the pupil; he sees a dozen other difficulties which ought to be troubling him but aren’t.

This phenomenon is today regarded as a cognitive bias called the curse of expertise (sometimes also called the curse of knowledge). It explains why great practitioners are not always great teachers, and why expertise - although often a reasonable heuristic - should not be what we look for in our teachers.

Learning from amateurs

Looking back at the historical picture, it is hard not to hold experts in the highest regard when it comes to teaching. The names whose teachings are passed onto us in school, from Archimedes to Newton to Einstein, are the foremost experts in their fields, whose innovations profoundly advanced our collective knowledge. The people we traditionally learn from directly, the teachers, professors and scholars, got to these roles by first earning recognition as experts from the institutions that publish their work or pay them to teach.

The growth of online education represents a major shift away from our reliance on experts for teaching. Today, some of the easiest ways to learn new information or tackle challenging topics are on sites like Khan Academy or Skillshare (not sponsored), educational channels on YouTube, podcasts, blogs, or any number of other corners of the internet. On all of these platforms, there is virtually no requirement for prior expertise, and also little to no startup cost, meaning that the only requirement for acting as a teacher to potentially millions of people is putting out educational content that people like.

Expertise as a concept is certainly still valued, but its importance has decreased a lot in the last few years, and will likely continue to do so as the online education space expands. This leaves us in a place where it is easy to overestimate the expertise of the people whose content we consume. Many of the people we learn from online are not experts, just people who learned a bit about something and were keen to share it with others.

You don't need to be an expert

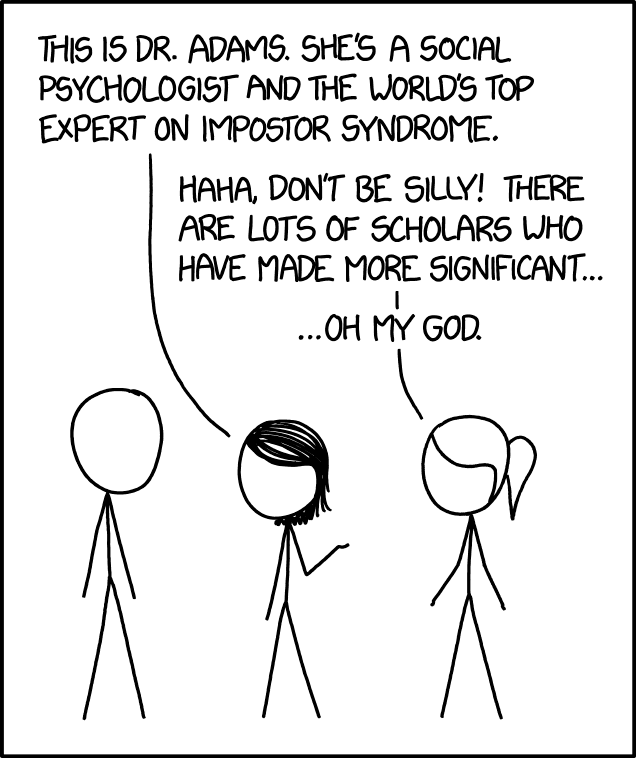

It's worth thinking about how these biases towards authority and expertise affect our own behaviour and self-expression. The curse of expertise can actually play into this quite directly - if you become become good at some new skill, for example, it's easy to forget how hard it was to get there, and effectively become acclimatised to your new ability level. As a result, you underestimate your own knowledge, and the value that you could provide to others as a teacher, thinking that you don't know enough to be worthy of trying to share your experiences with anyone else. This is closely related to the more well-known concept of impostor syndrome.

Austin Kleon's book Show Your Work! aims to break down the barriers that make us reluctant to share our art and ideas with the world, encouraging us to abandon this need to feel like we are qualified to do so:

Forget about being an expert or a professional, and wear your amateurism on your sleeve.

There's a YouTuber named Mike Boyd who I think embodies this sentiment perfectly. In his video series "Learn Quick", he documents himself trying to learn a difficult skill from scratch as quickly as possible, and in the process provides guidance on how one could follow in his footsteps (this video in which he learns to wheelie his bike for 100 metres non-stop is a particularly good one).

Today, there is virtually no material barrier to sharing your work or ideas with other people who might be interested in them - the only real barrier is your own willingness to put yourself out there.

I started this blog so that I would have somewhere to write down and share my thoughts whenever I feel like doing so, encouraged to by the various ideas discussed in this post. I hope you found some of it interesting, but don't take any of it too seriously - I'm not an expert, after all.

Thanks for reading!

I'd love to hear your thoughts – say hi on Twitter!